Not all shots are created equal. We know that. Whilst a speculative long-range effort with a crowd of players in the way is just as much a shot as is a David Nugent-style already-on-the-goal-line tap-in (if that reference has gone over your head then skip to 0:52 on this video for the finest finish you’ll ever see), the probability of Nugent scoring from three centimetres with nobody in his way is obviously high. It is these differences in chance quality that are exactly what expected goals models operate to capture.

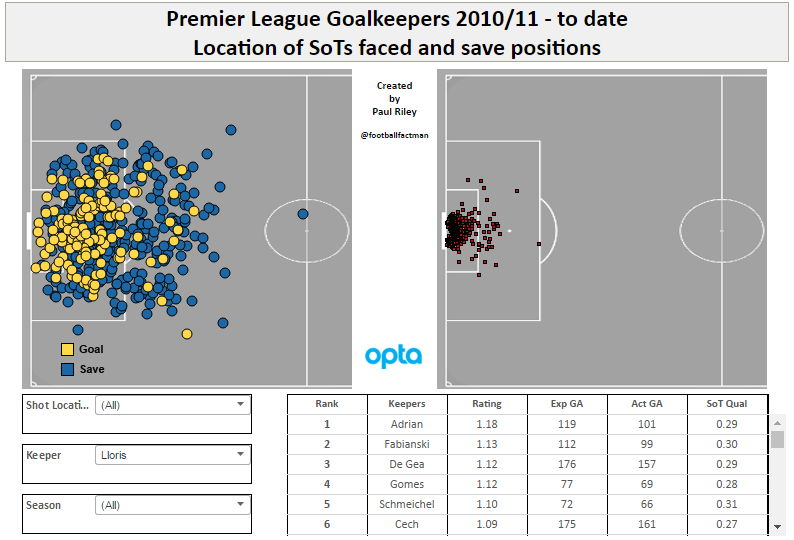

Not all saves are created equal, either. Paul Riley has done magnificent work in attempting to quantify save difficulty based on shot locations, and has recently made his data downloadable with a brilliant Tableau visualizing each keeper’s saving habits to boot.

Whilst Riley’s model captures save difficulty – the probability that a keeper will save a given shot – it overlooks entirely the save quality – was the ball caught, parried to safety, or parried to an opponent? This, I think, is an important addition to the debate. Catching saves guarantees possession and immediately alleviates defensive pressure. Parrying them to a teammate is okay but risky, whilst parrying shots back into the danger zone at the feet of an onrushing striker is to be avoided. Clubs should surely, then, be wary of any keepers with a tendency, upon seeing a shot that most other keepers would catch, to paraphrase Bruno Mars and conclude “I think I’m gonna parry you.” (I’ll get my coat…)

Dan Kennett has cultivated a substantial spreadsheet over the years documenting various goalkeeper actions, and he recently shared some data with me ahead of a podcast we recorded on Anfield Index along with Daniel Rhodes. A couple of the stats included were a goalkeeper’s ‘Catch to Parry Ratio’, and their ‘Safe Parry %’. Mixing the two numbers together enables us to consider, as a percentage, the proportion of a goalkeeper’s saves that are saved to safety (saves caught and parried to safety) and the proportion that they save ‘dangerously’ (those parried to an opponent).

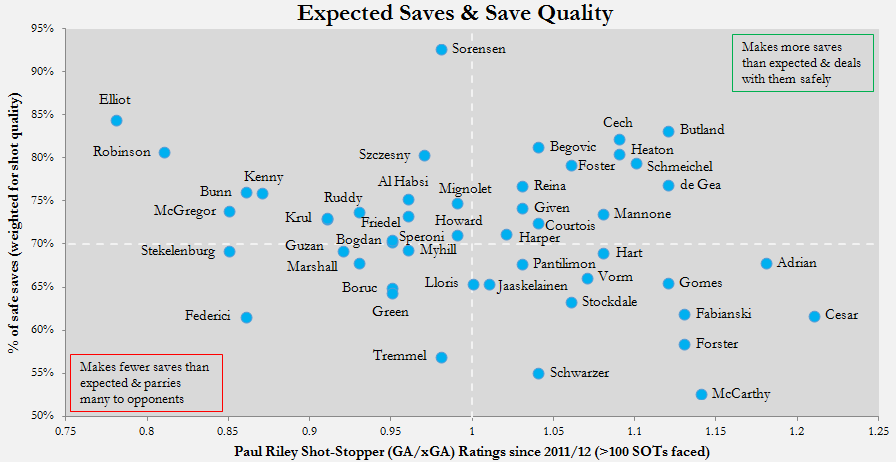

If we mix this data with that present in Paul Riley’s expected saves model, we are able to weight ‘save safety’ according to shot qualities faced, and then allocate goalkeepers into four categories. 1) Keepers like David de Gea and Petr Cech who make more saves than expected, and who tend to catch their saves or parry them to safety. 2) Keepers like Lukasz Fabianski and Adrian who boast a heady placing on Riley’s expected saves rating, but who have a concerning tendency to parry lots of their saves to opponents. 3) Keepers like Wojciech Szczesny and Rob Elliot who feature poorly on Riley’s rating, but who tend to catch or parry to safety those saves that they do make. 4) Keepers like Bournemouth’s apparently disastrous duo Artur Boruc and Adam Federici who save less shots than expected, and who parry to danger on the instances that they do stop a shot.

Looking at shot-stopping in this way throws up some interesting stories! Firstly, it seems like my most recent blog post may have been massively unfair on Kasper Schmeichel. Secondly, things look very healthy indeed from an English national team perspective. Whilst Fraser Forster’s impressive expected saves stats are hamstrung slightly by his proclivity for parrying (small sample size warning), Jack Butland, Tom Heaton and Ben Foster are all very impressively positioned.

++++++++++

Thanks for reading & please let me know what you think of this analysis! Fill up the comments below or give me a shout on Twitter!

3 thoughts on “Shot-stopping, ft. Bruno Mars”